It is estimated that 5,000 deaths are caused every year in England because antibiotics no longer work for some infections and this figure is set to rise with experts predicting that in just over 30 years antibiotic resistance will kill more people than cancer and diabetes combined.

Antibiotics are used to treat or prevent some types of bacterial infection. They work by killing bacteria or preventing them from reproducing and spreading. But they don’t work for everything. When it comes to antibiotics, take your doctor’s advice.

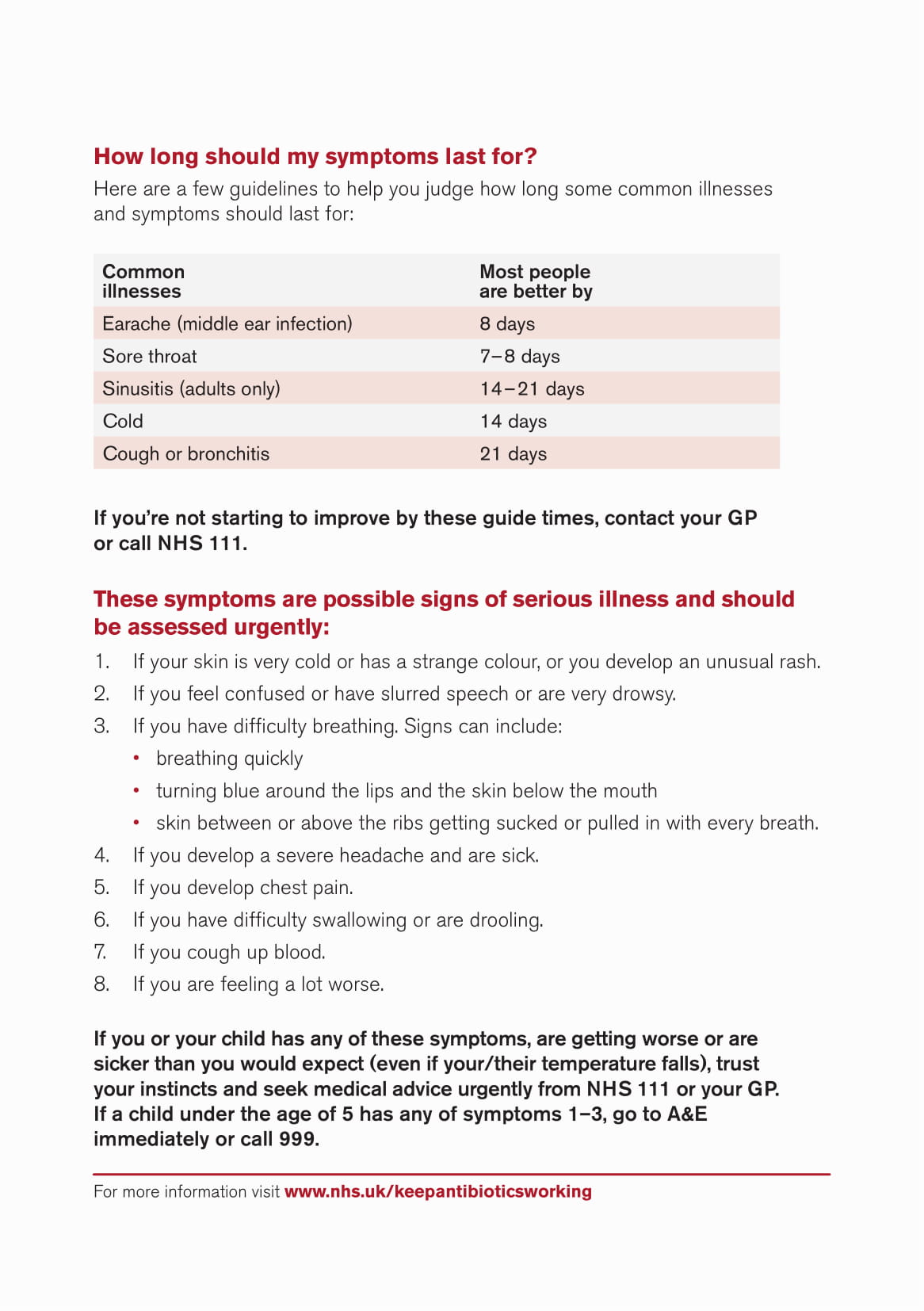

Antibiotics don’t work for viral infections such as colds and flu, and most coughs and sore throats.

Many mild bacterial infections also get better on their own without using antibiotics.

Taking antibiotics when you don’t need them puts you and your family at risk of a longer and more severe illness.

When antibiotics are used

Antibiotics may be used to treat bacterial infections that:

•are unlikely to clear up without antibiotics

•could infect others unless treated

•could take too long to clear without treatment

•carry a risk of more serious complications

People at a high risk of infection may also be given antibiotics as a precaution, known as antibiotic prophylaxis.

How do I take antibiotics?

Take antibiotics as directed on the packet or the patient information leaflet that comes with the medication, or as instructed by your GP or pharmacist.

Doses of antibiotics can be provided in several ways:

•Oral antibiotics – tablets, capsules or a liquid that you drink, which can be used to treat most types of mild to moderate infections in the body

•Topical antibiotics – creams, lotions, sprays or drops, which are often used to treat skin infections

•Injections of antibiotics – these can be given as an injection or infusion through a drip directly into the blood or muscle, and are usually reserved for more serious infections

It’s essential to take antibiotics as prescribed by your healthcare professional.

Missing a dose of antibiotics

If you forget to take a dose of your antibiotics, take that dose as soon as you remember and then continue to take your course of antibiotics as normal.

But if it’s almost time for the next dose, skip the missed dose and continue your regular dosing schedule. Don’t take a double dose to make up for a missed one.

There’s an increased risk of side effects if you take two doses closer together than recommended.

Accidentally taking an extra dose

Accidentally taking one extra dose of your antibiotic is unlikely to cause you any serious harm.

But it will increase your chances of experiencing side effects, such as pain in your stomach, diarrhoea, and feeling or being sick.

If you accidentally take more than one extra dose of your antibiotic, are worried or experiencing severe side effects, speak to your GP or call NHS 111 as soon as possible.

Side effects of antibiotics

As with any medication, antibiotics can cause side effects. Most antibiotics don’t cause problems if they’re used properly and serious side effects are rare.

The most common side effects include:

•being sick

•feeling sick

•bloating and indigestion

•diarrhoea

Some people may have an allergic reaction to antibiotics, especially penicillin and a type called cephalosporins. In very rare cases, this can lead to a serious allergic reaction (anaphylaxis), which is a medical emergency.

Considerations and interactions

Some antibiotics aren’t suitable for people with certain medical conditions, or women who are pregnant or breastfeeding. You should only ever take antibiotics prescribed for you – never “borrow” them from a friend or family member.

Some antibiotics can also react unpredictably with other medications, such as the oral contraceptive pill and alcohol. It’s important to read the information leaflet that comes with your medication carefully and discuss any concerns with your pharmacist or GP.

Read more about:

•things to consider before taking antibiotics

•how antibiotics interact with other medicines

Types of antibiotics

There are hundreds of different types of antibiotics, but most of them can be broadly classified into six groups. These are outlined below.

•Penicillins (such as penicillin and amoxicillin) – widely used to treat a variety of infections, including skin infections, chest infections and urinary tract infections

•Cephalosporins (such as cephalexin) – used to treat a wide range of infections, but some are also effective for treating more serious infections, such as septicaemia and meningitis

•Aminoglycosides (such as gentamicin and tobramycin) – tend to only be used in hospital to treat very serious illnesses such as septicaemia, as they can cause serious side effects, including hearing loss and kidney damage; they’re usually given by injection, but may be given as drops for some ear or eye infections

•Tetracyclines (such as tetracycline and doxycycline) – can be used to treat a wide range of infections, but are commonly used to treat moderate to severe acne and rosacea

•Macrolides (such as erythromycin and clarithromycin) – can be particularly useful for treating lung and chest infections, or an alternative for people with a penicillin allergy, or to treat penicillin-resistant strains of bacteria

•Fluoroquinolones (such as ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin) – broad-spectrum antibiotics that can be used to treat a wide range of infections

Antibiotic resistance

Both the NHS and health organisations across the world are trying to reduce the use of antibiotics, especially for conditions that aren’t serious.

The overuse of antibiotics in recent years means they’re becoming less effective and has led to the emergence of “superbugs”. These are strains of bacteria that have developed resistance to many different types of antibiotics, including:

•methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)

•Clostridium difficile (C. diff)

•the bacteria that cause multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB)

•carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (CPE)

These types of infections can be serious and challenging to treat, and are becoming an increasing cause of disability and death across the world.

The biggest worry is that new strains of bacteria may emerge that can’t be effectively treated by any existing antibiotics.